Have you ever been making your morning cup of coffee and out of your groggy mind-state crawls the thought,

“I wonder how much energy I’m using to make this coffee every day?”

Well, we at SolarMill sure did, and gosh dang it if we didn’t just have to find out.

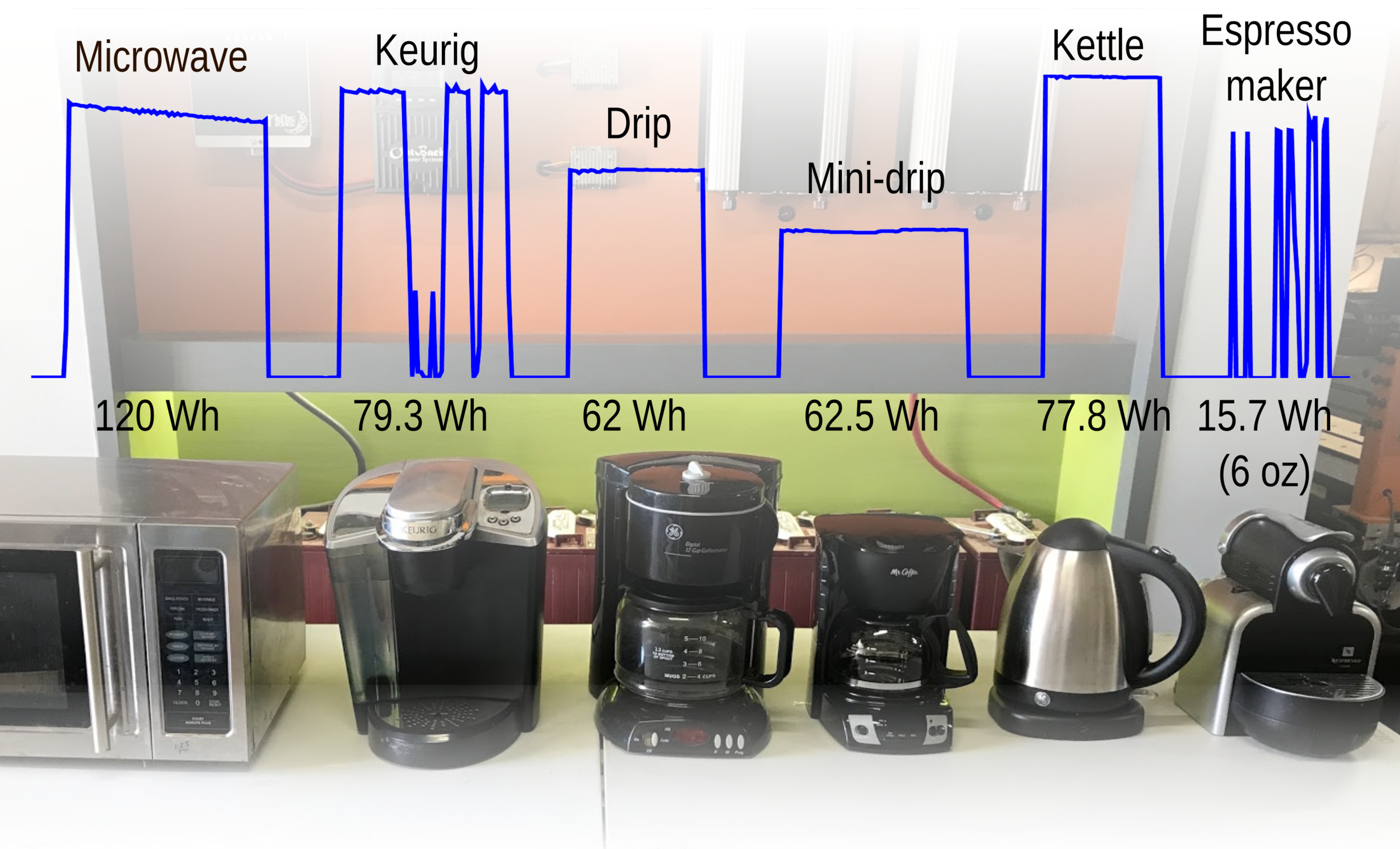

We lined up every coffee-making device we could get our hands on (standard drip maker, mini drip maker, Keurig, electric kettle, espresso maker, and a microwave) and set out to test our way to an answer.

We ran each of the machines through a number of trials, tracking energy consumption and temperature to find the energy consumed per ounce of coffee as well as sheer efficiency at heating water to brewing temperature.

Below you’ll find a graph mapping the energy consumption of each device to produce the equivalent of 3 total servings of coffee so we could take an average. We found that in the most likely of scenarios, such as using a drip maker or a Keurig, it takes about 20-27 Wh (Watt hours) for a standard 8 ounce cup.

But only after a series of slightly obsessive side-tracks and top-rate reflections did we finally get to the bottom of things, to see that there are a whole lot more factors involved than we expected. For example, we found that while the regular old drip maker is actually the most energy efficient per ounce of coffee, the espresso maker was most efficient per milligrams of caffeine.

We also discovered there's no way to effectively clean a pod style coffee maker, and after disassembling ours, found it riddled with mold and scale.

Yum.

Needless to say, I think we'll stick with other methods. We consider the electric kettle with french press or pour over maker the best method all around. Not only is it a close second in terms of raw energy efficiency, but it's the only solution which can be thoroughly cleaned and totally disinfected. And, owing to the stainless steel mesh filter, the French Press has the least amount of waste- only the grounds are left over and they can be composted. Considering that the electric kettle can also be used for tea or to make ramen, this versatility adds to its appeal and that makes it a winner in its own respect.

In the end, perhaps coffee wasn’t even the point at all. It's really about establishing a methodology for measuring the energy used to perform a task, any task, whether that is making a cup of coffee or producing one of our eco-friendly products. There are certainly other factors to consider, like the embodied energy of the materials and total product life cycle, but we have chosen to limit our study to the processes and transformations that happen on-site, under our roof, and under our control.

You can read the full research here outlining our caffeine-fueled hijinks, including data, methodology, what the heck a Watt-hour is, and musings on a sandwich-powered energy grid.